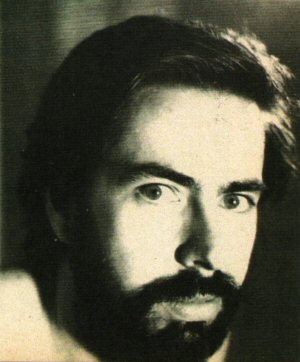

Article: Ed

French

Fangoria Magazine No. 26, 1983

By Bob Martin

After a decade

of acting and stage makeup, he switched careers to become a 30-year-old

"newcomer"' in makeup effects.

Ed French has spent most of his adult life working (or finding work)

as an actor. In that time, he's met with a measure of success-at least

enough success to keep him plugging away for over a decade. Throughout

that same decade, makeup has been almost a "side interest" to French,

though a very useful one. Today, at 30, he is a practitioner in the art

of what he calls "makeup illusions," a term devised by Dick Smith for

his credit in Ghost Story. And for the first time, French has been able

to make a living by doing something that he loves.

French was born in Boston, and raised in Pelham, New Hampshire, a tiny

town by most standards, though one of the largest in that underpopulated

state. "There weren't many movie houses around" recalls French, "but my

babysitter would take me to see Elvis movies, now and then. I thought

she had terrible taste. But I remember very clearly the day I first saw

a movie that made a big impression on me. I remember that I was in firstgrade,

and I was being kept in the house because I was sick. It was winter, and

I remember looking out the window at a snow fort some kids had been building

in the parking lot across the street, and how much I wanted to go out

and play in that fort. That was the day I first saw Bride of Frankentein

on TV, and the one scene that I recall very clearly from that day is where

the monster climbs up to the top of the tower and throws Dwight Frye off.

It no doubt affected the course of my whole life."

Young French soon developed an affinity for other classic monsters of

the Universal era, and in a few years had begun his first experimentations

with makeup.

"I found the Corson book, Stage Makeup, in the school librarywhen I was

a freshman in high school," he says, "and was particularly struck by the

makeup developed for Hal Holbrook's performances as Mark Twain. I was

about 13 or 14 at the time, and got totally ahead of what I was supposed

to be doing-I really wanted to try the ambitious stuff. So I went home

one afternoon, and put my brother, who must've been about 6 years old,

to work, doing a life cast of my face.

"Well, that experience probably set my makeup career back several years.

I had him just dump the plaster on my face, and I spent about six hours

trying to get it off, and I subsequently had to learn how to pencil in

missing eyebrow hairs.

"I didn't attempt lifecasting, or any sort of postrhetic again for a

long time after that, unfortunately. I did get ahold of Dick Smith's Monster

Makeup Handbook, and used that for a lot of school plays, but I didn't

try anything of that nature again until 1976."

While makeup remained an important part of French's life, during high

school he decided upon a career as an actor. He felt he'd come a little

closer to that goal when, as a high school senior, he was hired as an

announcer at a small radio station of mixed formats. French was promoted

from the Mantovani shift to the easy listening morning show to night-time

rock. "But I found that the audience really didn't want to hear me read

H.P. Lovecraft and Ray Bradbury; they wanted to hear the music. So, I

Wandered i nto summer stock, where makeup skills were very helpful to

me. I was one of the few apprenticeswho could parkcars, and rush back

in before the curtain was up, get into full makeup and beard, and be on

stage as an extra in the opening scene of Fiddler on the Roof."

Many of French's most challenging roles over the next decade involved

his makeup skill as well as his acting talent, including his favorite

character, from Ferenc Molnar's The Play's The Thing. "The character in

the play is a former matinee idol," he says, "now in his late 50's, a

hopeless alcoholic and womanizer. it's the sort of role that always came

to me in repertory, because of my makeup skills. The character is a horrible

man, but I succeeded in getting a combination of comedy and pathos into

the role that was particularly satisfying." The makeup French developed,

with the director's encouragement, was French's first prosthetic work

since his nightmare experience as a teen.

By the late 70's, French had done a good deal of work in repertory, and

had gone to England as part of an American review, Feiffer's People, based

upon the cartoonist's work. He had played lead roles in works by Shakespeare,

Stoppard, Chekov, Williams and Molnar, and in a repertory production of

the Feiffer play Little Murders, French developed for one of his fellow

actors rubber zits that could actually be squeezed to erupt over the heads

of the audience.

But, despite such high points, French became restless in his chosen career.

I still love stage work," he says. "But when you're doing stage, you might

rehearse for a month and then perform for another month. And by the time

you're two-thirds through rehearsals, you know whether you're wasting

your time or not-and if you are are, you're stuck."

One of French's final efforts to stay active as a theatrical performer,

without feeling "stuck," was a one-man show he began to develop around

the Harlan Ellison-edited story collection Dangerous Visions. Unfortunately,

Ellison seemed, by French's account, to perceive the project as competition

for the author's own readings, and as a possible hazard to radio and TV

deals for the material. "I told him that I saw this as an opportunity

to bring these works to a different audience, not just the knowledgeable

fans, but to a theater audience. I invited him to come up and see me rehearse

it; I said, 'I think you'll like it.' He said, 'Don't bust my chops.'

I said, 'Bye.'"

"Anyone who is reading the magazine and wants to know how to start doing

makeup should know that the first thing to do is make friends with the

folks at Alcone, the New York makeup supply house. Beth and Sharon are

very nice people; I've been buying from them since I was a kid in New

Hampshire, but I've only been going in there regularly since 1980. They

recommended me for a job, which led to a series of jobs, doing medical

simulations for an ad agency that had a number of medical clients. They

said they needed an open sore on a foot, and asked to see my portfolio.

I didn't have one, so I said that someone else was looking at it . . .

. 'But I just happen to have my kit here with me,' I said. 'Show me a

picture and I'll copy it,' and I took off one shoe and sock and applied

the sore to my foot."

More agency work, including medical simulations and some cosmetic work,

followed. One early film-related job involved suitably bizarre makeups

for the poster advertising the re-release of The Incredible Torture Show,

retitled Bloodsucking Freaks (see Fango #16, "Monster Invasions").

French's first film assignment was for Smithereens the story of a young

new waver searching for punk success. French appeared in the film, thoroughly

disguised as a Bowery Bum, and was assigned by director Susan Berman to

create a brief sequence, a film within the film that would parody a low

budget horror movie. Cookie Mueller, a veteran of Andy Warhol's filmmaking

factory, played opposite French in a brief sequence that had Mueller terrorized

by a slime-lobster, and ends with a pair of scissors in French's left

eye. "Working with Cookie Mueller was quite an experience," recalls French.

"I remember, the night we were shooting, I was standing there with a pair

of scissors in my eye and she turned to me and said, 'I can't believe

it! I'm up at 4 A.M. and I'm not even drunk!"

Another small movie project followed- the sequences filmed in New York

for Nightmare. "There were way too many people working on that; it was

complicated far beyond what was needed. Les Lorraine had done all the

casts; I worked on the innards of the decapitated figure, and painted

that figure, and dressed and painted the head of the guythatgetsthe axe,

which came in looking, literally, like a football. Savini was brought

in when it was realized that there was no one around who knew how to stage

and photograph an effects sequence.

"We had three dummies of the woman, for that number of takes, and the

boy who was to play the young murderer came in and was handed the fake

axe. He swung at her from the back and hit her in the shoulder; the head

came off and the blood came squirting out-wrong. The producer came in

and said, more blood on the next take, and we told the kid, swing a little

higher. On the second take, he hits it square in the head and knocks the

head across the room. Blood squirts all over everybody. We set up the

third take-there's plastic laid over everything and everybody. The producer

comes out and says, 'I want more blood, this time I'm gonna pump the blood.'

it's my job, I promise him I'll hit the ceiling this time. Meanwhile the

kid is about to hit the last dummy; Savini goes up to him and asks, 'Do

you wear glasses?" The kid wears glasses, and no one had thought to ask

him. For the last take he wears the glasses, hits the mark and the blood

hits the ceiling. That's the take they needed."

Thanks to his friendship with the people at Alcone, French was able to

leave a unique calling card at the supply house -an "Elephant Man" mask

he had sculpted and built, using photos of Merrick in existing reference

works as his guide. John Caglione saw the mask on display at Alcone, and

contacted French to join his Amityville II crews.

"If I went into Amityville with a 30 on the scale of knowingwhat there

isto know about this kind of makeup work," says French, "afterwards it

was up to about 90. I did lab work, mostly, running foam. But I learned

a great deal from John.

"It was certainly my first experience working on a movie where they had

money to burn. There were several stages of the possession makeup, and

John would work hours on a particular stage. He'd finish, and they'd say,

'We've decided not to shoot that scene right now-we need him in a different

stage.' He'd tell them that it would mean anotherfive hours in makeup,

and they'd say 'Okay, we'll do it your way,' and they'd do the scene they

intended to do, using the wrong stage. But they had a brilliant editor

who managed to salvage a number of things -not everything."

Another French technique forfinding work is his use of picture postcards

featuring his work for all mail communication. One such postcard interested

Bill Bilowit, a prop designer from the Creepshow crew, now art director

of Sleepaway Camp. Bilowit approached French with a series of storyboards

outlining the effects for the movie. "If I hadn't done Amityville II,

I don't know that I would have been able to do Sleepaway Camp," French'

says. "I probably would have taken the job, struggled my way through it,

and would have hated the work. But I enjoyed the work, and for that I

am very grateful to John and Stephan.

"In its graphic approach, I would say that it's like The Birds. Early

on, the director, Bob Hiltzik, and I sat down and discussed the fact that

if we were to shoot things in the straightforward way that they're usually

done, then my work would get cut, their film would be edited, and nobody

would be getting any entertainment value out of it. Still, the payoff

on these murders is seeing something terrible happen. You won't necessarily

lose your popcorn, but we did manage to portray a number of terrible things

happening.

"For instance, in one scene, a character is in the middle of delivering

a line when [CENSORED TO PRESERVE SHOCK]. I don't think any movie has

ever had that happen before."

French, working in the confines of his New York apartment, was able to

supply all the victims required for the summer-camp stalker movie for

an incredibly low budget. Word of his efficiency soon reached the producers

of a proposed low-budget fantasy film entitled Tales from the Black Forest,

inspired by some of the more grisly moments from the stories of the Brothers

Grimm. At this point, only one of the three stories planned have been

shot, while the producers seek additional financing.

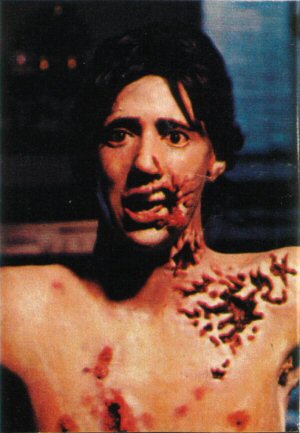

The one episode, however, promises a transformation sequence unlike any

seen before, as any army of worms becomes flesh to adorn the dry-rotted

skeleton of an ancient witch. "The final makeup was a six-hour ordeal

for the actress, Leslie Sank," says French, "and she handled it very well-and

gave a fantastic performance."

Patience is advised to those anxious to see French's work in Smithereens,

Sleepaway Camp, Geek Maggot Bingo (see "Monster Invations," issue *25),

and Tales from the Black Forest. The first of these, now in release from

New Line, is not planned for wide distribution; the next two are yet to

be announced for release, and the last has yet to be completed. But, even

if these movies never make it to the local theaters in Nashua, New Hampshire,

several scripts sit on his shelf that may become his next project; and

French is one of the few people who knows any details on Frank Henenlotter's

anxously-awaited second feature-which may prove to be French's second

assignment with John Caglione. "Frank gave me a book containing a number

of pictures, to draw a concept from," he says, with the proper air of

mystery.

You

may take it as a warning, or as a promise: we have not seen the last of

Ed French.

|